It’s infuriating when you know something and can’t quite call it to mind. Both Wittgenstein and Freud wrote about this situation, but they were interested in different aspects of it, and they went in very different directions. Wittgenstein focused on situations where a word seems to be on the tip of our tongue but we struggle to get it out. Freud analysed the situation when a name escapes us during a conversation. So, what did they each conclude, and how do their conclusions relate to each other?

Wittgenstein’s discussion was sparked by the suggestion of the American philosopher and psychologist, William James, that when a word is on the tip of our tongue, we experience a gap that only one word can fill. It is as if we experience the growth of a word. The word is not yet there, but in a certain sense it is, or something is there that cannot grow into anything other than that word. This seems very mysterious. But the cause of the mystery is the temptation to treat the words “it’s on the tip of my tongue” as the description of an experience. In fact, the words are a signal. What makes them interesting is that they are frequently followed by the individual finding the word they say they wanted (past tense) to use.

Wittgenstein summarises his conclusion: “The word is on the tip of my tongue.” What is going on in my mind at this moment? That is not the point. Whatever went on was not what was meant by that expression. What is of more interest is what went on in my behaviour. “The word is on the tip of my tongue” tells you: the word which belongs here has escaped me, but I hope to find it soon. For the rest, the verbal expression does no more than some kind of wordless behaviour.” (PI part 2 §298)

For Wittgenstein, the interest in this phenomenon is the link with rule-following (someone saying: “I know how to go on”) and with phrases such as “when I said X, I meant …” or “when I did X, I was intending to …”. In all of these cases, what matters is that people are (normally) able to follow the phrase with an appropriate action (they provide the word they were looking for, they continue the series, they explain their statement/action). Within these language games, the individual’s (sincere) statements are treated as having a special status. Only they can definitively say what word was on the tip of their tongue, how they intended to continue the series and what their meaning or intention was. Someone else may make a suggestion, but if the other person rejects that suggestion, that was not the word that was on the tip of their tongue.

Freud is interested in the related but slightly different situation, when in a conversation we are talking about someone, but their name unexpectedly escapes us. He gives an example from his own life (“The Mechanism of Forgetfulness”, Vol 3 Collected Works). He was on a carriage drive in Herzegovina with a companion and talked about the peculiarities of the Turkish inhabitants that lived in that area and then about some paintings he had admired in the Italian city of Orvieto. But he could not remember the name of the artist who had painted the Last Judgement frescoes. Was it Botticelli or was it Boltraffio? A few days later, he met a cultured Italian who put him out of his misery by telling him what he already knew – the frescos were painted by Luca Signorelli.

A common enough occurrence that we can all sympathise with. But Freud is determined to explain it. He starts by examining the context, and he finds what he believes is an important clue. During the first part of his conversation something had been on his mind that he had not wanted to share with his companion. He had told him an anecdote about the local Turkish people’s great respect for doctors, but he had not mentioned another anecdote he had heard at the same time, which suggested that sexual pleasure was so important to these people that, if it came to an end, they were ready to die. Consciously or unconsciously, Freud felt this was not an appropriate anecdote to share on a pleasant drive in the country.

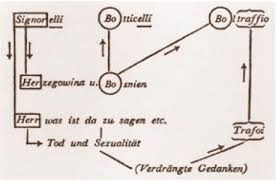

Having to his satisfaction identified the repressed idea (death and sexuality), Freud searches for clues as to what might have caused his memory lapse. He rules out the affinity in content between the Last Judgement frescoes and death and sexuality on the grounds that this link “seems to be very slight”. Furthermore, since he forgot a name, he thinks it is “probably that the connection was between one name and another”. Working back from the forgotten name, he notes that Signor means Sir or Herr in German and that this links to the name “Herzegovina”, which is the province about whose Turkish inhabitants he repressed one anecdote. Furthermore, the word “Herr” figured prominently in both anecdotes. He thinks this provides evidence that the repressed idea of death and sexuality (with its link to an anecdote about the Turkish inhabitants of Herzegovina) was the cause of his not being able to remember the name of Signorelli. He thinks that further support is provided by the two incorrect suggestions he was able to come up with (Botticelli and Boltraffio). Both start with “Bo” which links with the name Bosnia, which is almost synonymous with its neighbour, Herzegovina. And the ending of the second suggestion resembles the name of the place (Trafoi) where Freud learnt of the suicide of a patient due to an incurable sexual complaint.

Freud provides a diagram illustrating his causal explanations.

Wittgenstein’s account seems hard to object to. As he suggests, we could imagine a wordless version of the phenomenon he discusses. Someone is speaking, pauses, looks irritated with themselves and then completes their phrase. No one is going to challenge how they completed the sentence or claim that they had no idea what they were going to say when they started to speak. When someone starts to speak, we assume that they have something to say and, unless they say that they changed their intention in the course of speaking (or we have reason to think they are trying to deceive us) , we accept that the sentence they utter is the one they intended to utter from the start. Someone might challenge the phrase “the word was on the tip of my tongue” and insist that we say: “I’ve got word fog”. But the phrase is just a signal, so this does not really matter.

The situation is different in relation to Freud’s account, since he thinks he has identified both the general causal mechanism that leads us to forget words/names (associative link to a repressed idea) and the specific chain of causes that led him to forget the name “Signorelli”. Freud’s account is very impressive, but it is hardly a scientific proof. His starting point is his non-sharing of the anecdote about death and sex. But how can we (or he) be sure he has identified the correct “repressed” idea? In contrast with the word-on-the-tip-of-my-tongue situation, we cannot say: “it’s Freud’s mind, so if he says it was the causally effective repressed idea, he must be right”. We need independent evidence if we are going to assign an explanatory role to a specific idea. This is clearly true in relation to a putative causal explanation. But it is also true in relation to an explanation in terms of reasons. If a friend seemed uncomfortable and strangely circumlocutory in conversation, we may be able to work out the words or ideas they are trying to avoid, but multiple examples of then avoiding the natural way of putting things (or other examples of them acting strangely), would provide the evidence for the claim that there was a conscious (or unconscious) reason for their strange behaviour.

Freud does an impressive job in linking the name Signorelli to what he claims is the repressed idea. His analysis has a Sherlock-Holmes-like impressiveness, but it illustrates what a strange game he is playing. The potential associative paths from the name “Signorelli” are pretty much limitless. If we can use anything Freud has ever said, thought, read or done, we can probably find multiple ways of making links between this name and any general idea he might have had. Obviously, Freud himself could provide endless possible associative links, but, even without him, it is easy to provide possible alternatives. Maybe he had unconsciously been thinking that his companion was like a demanding child, a little master (Herr), and he had been unable to name Signorelli because he was worried he might betray this unconscious thought.

Maybe he had (consciously or unconsciously) been thinking about how superior he was to his co-author, Josef Breuer, and this prevented him from mentioning Signorelli whose successes were overshadowed by the genius of Michelangelo. Perhaps, when he suggested Botticelli, this was a compromise between his wish to emphasise his superiority to Breuer and his unconscious guilt about this. But then he felt the compromise was too generous, so fell back on Boltraffio, not a genius but someone who worked with one. It is a great game to play, but there are countless possible links, and it is not clear on what basis one could definitely identify one set as the correct one. Furthermore, and in contrast to the word-on-the-tip-of-my-tongue phenomenon, there is no basis for assigning to the individual concerned (in this case, Freud) a privileged role in determining the correct answer. That’s just not how causal accounts work.

So, what should we make of all this? One obvious difference between the two accounts is their aims. Wittgenstein is seeking to clarify our psychological concepts. He does not offer explanations. Instead he seeks to make clear how our psychological concepts work (and eliminate confusions about how they work). In contrast, Freud wants to develop a causal account of the mind. He is committed to the idea that there are causal explanations for everything we say and do – not just the forgetting of the name Signorelli, but also the incorrect suggestions of Botticello and Boltraffico. He believes that lots of complicated processes take place in our minds, although he accepts that they cannot be investigated empirically and that the only gateway to them is via consciousness. However, he thinks this route only provides limited and unreliable access to them. But these assumptions make it impossible to offer a definitive account of the supposed mental processes. There is no way of deciding between different putative explanations. But if there is no way of knowing anything about these processes, on what basis can we be sure that they exist? How can they provide explanations if the only evidence for their existence is the phenomena that they are supposed to be explaining?

Leaving aside the issue of whether there is any evidence for the existence of the mental processes that Freud believes in (and indeed whether talk of such processes actually makes sense), it is clear that his approach cannot lead to the identification of causes. His account rests not on independent evidence, but on a chain of reasoning whose force lies in the ingenous links it manages to forge between different ideas. It’s a tour de force, but it’s not objective evidence for a causal explanation.

This argument about causal explanations does not exclude the possibility of explanations in terms of the unconscious. However, like our everyday explanations in terms of reasons, these explanations need to be based on detailed evidence related to what the individual said and did, not on ingenious speculation. Furthermore, there is no guarantee that every aspect of what we say and do can be explained in this way. Sometimes a memory lapse is just a memory lapse. It is possible that Freud forgot Signorelli’s name because he felt guilty about the pleasure he got from his belief that he was far superior to Breuer, or he might have forgotten the name because he was unconsciously worried that he was Signorelli rather than Michelangelo. Or maybe he just forgot a name. It is something that happens to all of us (and increasingly as we get older).

Leave a comment